The opening pages of the 1877-1878 report from the Superintendent of Lighthouses in British Burma reads like a novel:

The opening pages of the 1877-1878 report from the Superintendent of Lighthouses in British Burma reads like a novel:

“The most noteworthy event in the history of the year was the total destruction in 1877 of the Krishna Shoal light-house , on the south coast of Pegu.”

While this report was extracted from the “Proceedings of the Commissioner of British Burma in the Revenue Department”, it contained these wonderful narrative and descriptive elements:

“This light-house, built throughout of iron, and supported on screw piles, stood on the south-eastern point of the shoal from which it takes its name, the depth of water round it at low water being three fathoms, with a rise and fall of 12 feet, and a tide running six knots and hour. It was begun in 1868 and completed in May 1869 at a cost of 16,000 pounds , the light being shown for the first time on 10th June in the latter year.”

Previous inspections suggested vulnerability due to scouring, and while subsequent repairs were carried out by the Public Works Department, they proved insufficient. Another noteworthy event that year, (though apparently not the most noteworthy) was the murder of Mr. E.R. Woodcock, “the only European ligthkeeper stationed at Table Island lighthouse,” by one of the “menial employees” there. There were both civil engineering and criminal mysteries to unravel in this tale!

I came across this Report on Lighthouses off the Coast of British Burma in the India Office Records at the British Library. Thought it was before my grandfather’s time working on lighthouses there, I read these pages with deep interest for the texture they contained. John O’Brien, the archivist of the India Office Records, shared with me that many of the reports and correspondences of the 19th century carried a level of detail that later ones in the twentieth century lacked.

I was curious to know if similar accounts existed for public works projects in Burma in the 1920s and 1930s. O’Brien pointed me to an index of the Proceedings of the Government of Burma, Public Works Department which contained reports of correspondences until 1924. I requested the volumes from 1919-1924. In each of these volumes there was a section called “Establishment,” which included notes about engineer appointments and transfers, as well as a section on “Accounts”.

In the Establishment section, I once again discovered my grandfather. First- when he was appointed to the department- “Narayanan, Mr. M.S. Appointment of –as a Temporary Engineer.” Next when he is transferred to a different post: “Narayanan, Mr. M.S. Assistant Engineer. Order transferring from the Pegu to the Maritime Circle.” Later when he was granted “ an extension of time in which to pass the lower standard examination in Burmese.” And then again, regarding a nominal raise: “Narayanan, Mr. M.S Assistant Engineer Superintending Engineer, Maritime Circle letter No. 4010-14E (N. 10) dated the 6th May 1921recommends that sanction be accorded to grant of the first annual increment of Rs. 20 per mensem to the pay– with effect from the 1st February 1921.” These proceedings also provide a glimpse of the disparity instilled in colonial rule like the inequity in pay between Indian engineers and European engineers of the same rank.

The British Library does not have the records contained in the file numbers referenced in these reports. These proceeedings were often copied to London, but the enclosures referenced were not sent. It is possible the records are still in the Rangoon or the Delhi archives, if they survived.

These proceedings in the 1920s did not have the narrative quality of the 1877 lighthouse report, yet there is still a narrative to be assembled from various fragments. There is truth to the adage that if you want to know what is going on in a place, you should follow the money. While accounting and budget reports may not seem like riveting reading material, they do provide a window into what was happening where and when. With my earlier research going through the civil yearly lists, I had established a spreadsheet tracking where my grandfather was posted in Burma and when. From family stories, I’ve been told he worked on bridges, lighthouses and roads. A list of and budget for public works in region can be found for each year, so I can cross-check between the station listed in the civil list and the annual public works budget for that station to discover the division or range of projects he could have worked on while stationed in that place.

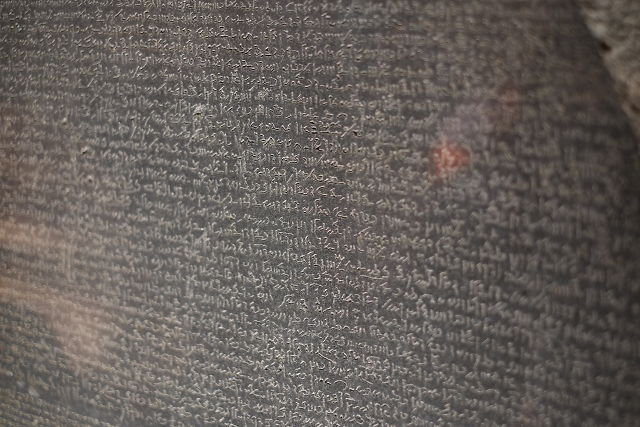

During this trip to London, I also had a chance to pop over to the British Museum, which houses the Rosetta Stone. It was amazing to see this artifact up close. The top portion contains the traditional Egyptian hieroglyphics, below it is the translation into Demotic, the everyday Egyptian, and at the bottom is Greek, then the government language. In some way, I felt the notes I was compiling from this research at the library was like developing a Rosetta stone of my own, a means of deciphering the language of government records.

As a geotechnical engineer by training, I’m familiar with coming home dirty after a day’s work. I didn’t expect a similar experience after a day at the library unearthing these records. These dusty volumes of proceedings caused my eyes to water and my nose to run. I had rested these books momentarily on my lap to flip through pages, and my hands and pants were subsequently stained a rust like orange, reminiscent of time spent around tropical residual soils and iron-rich laterite roads. Despite my allergic response, this pleased me slightly and made me feel like I was no longer in London, but closer to Burma.

Read earlier posts from the British Library:

Dispatches from London: An Introduction to the British Library

Researching the India Office Records at the British Library: Time and Timelines

Many thanks to the Jerome Foundation for a Literature Travel Grant to support this research.