Tonight I attended this discussion that examined the similarities and differences between what is happening now in Egypt with the 1988 student uprising and the 2007 Saffron Revolution in Burma.

The discussion covered the socioeconomic conditions of the two countries, the role of the military and the role of social media.

The poverty and unemployment rates in Egypt were presented and compared with Burma where 90% of the people live below poverty. Burma has high infant mortality and child malnutrition as well. In Egypt most households have electricity and water, which is not the case for Burma. Out of the 80+ million people in Egypt, about 21 million are internet users, and 55 million people have access to cel phones. In Burma, in 2004 it was estimated that less than one percent of the 55 million population had access to the internet, though that number is increasing due to more internet cafes.

One member of the audience noted that Gmail and Facebook can be used, but yahoo is locked. Only secure web addresses are allowed.

Another gentlemen noted that in Egypt there is a common language of Arabic and there is a more digital media equipped to handle Arabic. In Burma, there are many languages, and harder to both communicate within the country and outside. English used to be spoken more (especially in the 1988 uprising). He also noted the difference between literacy (read, write and think) and functional literacy (read and write, but not think), which is what the military Junta advocates.

In the comparison of the two military forces, the big difference is that the Egypt’s military sided with the people instead of the government. Soldiers in Egypt, receive a basic education, that includes political perspectives, and an understanding of the world. Egypt requires compulsory military service, so perhaps that is why people respect the military, because all of their family members too had to serve.

In Burma, the military is large ( ~500,000) but that number is in decline. Burma holds the largest number of child soldiers in the world (~70,000, from 2007 HRW). Military used to maintain power. They go through psychological training. The military recruits orphans and children of rebels. (Mention of ‘Tiger Schools’).

Nay Tin Myint, of the National League for Democracy ( Aung San Suu Kyi’s Party) was there to talk about the 1988 Uprisings. He was a student at Rangoon University at the time.10,000 people had died, and there was no newspaper/tv coverage of the incident. There was no contact with the outside world.

They were able to end the Ne Win Regime. But even after the 1990 Elections, which Aung San Suu Kyi won, the military put her under house arrest, arrested other political prisoners and held power.

Someone had asked, why did the activism seem to stop then. Nay Tin Myint said, that those who continued were beaten and jailed. He spent from 1989 to 2005 in jail., seven of those years in solitary confinement. There was lack of medical attention, lack of food. He was shackled and tortured daily.

The Military Junta employed a Four Cut Campaign ( cutting communication, food, resources, …)

But people still managed to communicate. Another man discussed, the codes, he would use to meet up with someone. His friend might scratch a lamp-post to indicate he wasn’t home, and he would leave a mark indicating he stopped by.Another way of organizing was by creating literature study groups and sharing books.

It was noted that 1988 uprising was inspired by 1986 events in Philippines. And 1988 in Burma inspired 1989 in Tiananmen Square which later influenced Timor/Indonesia. (Just like Tunisia Inspired Egypt which is spreading elsewhere now too).

Nay Tin Myint noted that when he was release in 2005, other political prisoners too had been released and they were able to communicate with outside press, BBC, VOA, and Democratic Voice of Burma. All of these are foreign radio stations. Internal radio stations are censored.

Two monks were in attendance and one discussed the 2007 Saffron Revolution. He said that the number of monks in Burma roughly equals the number of soldiers. The monks often come from rural areas and from the low to middle classes.

He noted three things that need to change in Burma.

1.) The low ranks of the military live in poor condition and receive poor education. It is important to educate them and change their ideology. Perhaps then, they will stand with the people of Burma.

2.) Need technology and more access to Phone/Email/Fb.

3.) Take the opportunity to turn momentum into the Next Revolution He noted that in 1988 they missed the opportunity to form an interim government. It would be important not to miss this the next time.

Open discussion talked about getting more books translated into Burmese language. Technology may be changing the way we transfer books too.

Discussion of music. In Burma, “Dust in the Wind”, was a revolutionary song. There is a strong Hip Hop movement in Burma today.

Folks from Digital Democracy were present and they noted that while social media has lots of potential, you have to be careful with it too. It might be an easy way for a government to find out all the leaders of a movement and target them.

Hopefully the discussion will continue soon, and wonder what Malcolm Gladwell would think if he was here.

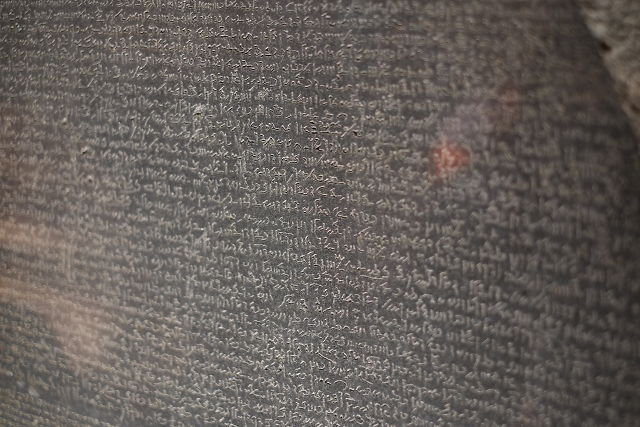

The opening pages of the 1877-1878 report from the Superintendent of Lighthouses in British Burma reads like a novel:

The opening pages of the 1877-1878 report from the Superintendent of Lighthouses in British Burma reads like a novel: