Last week, I had a chance to see

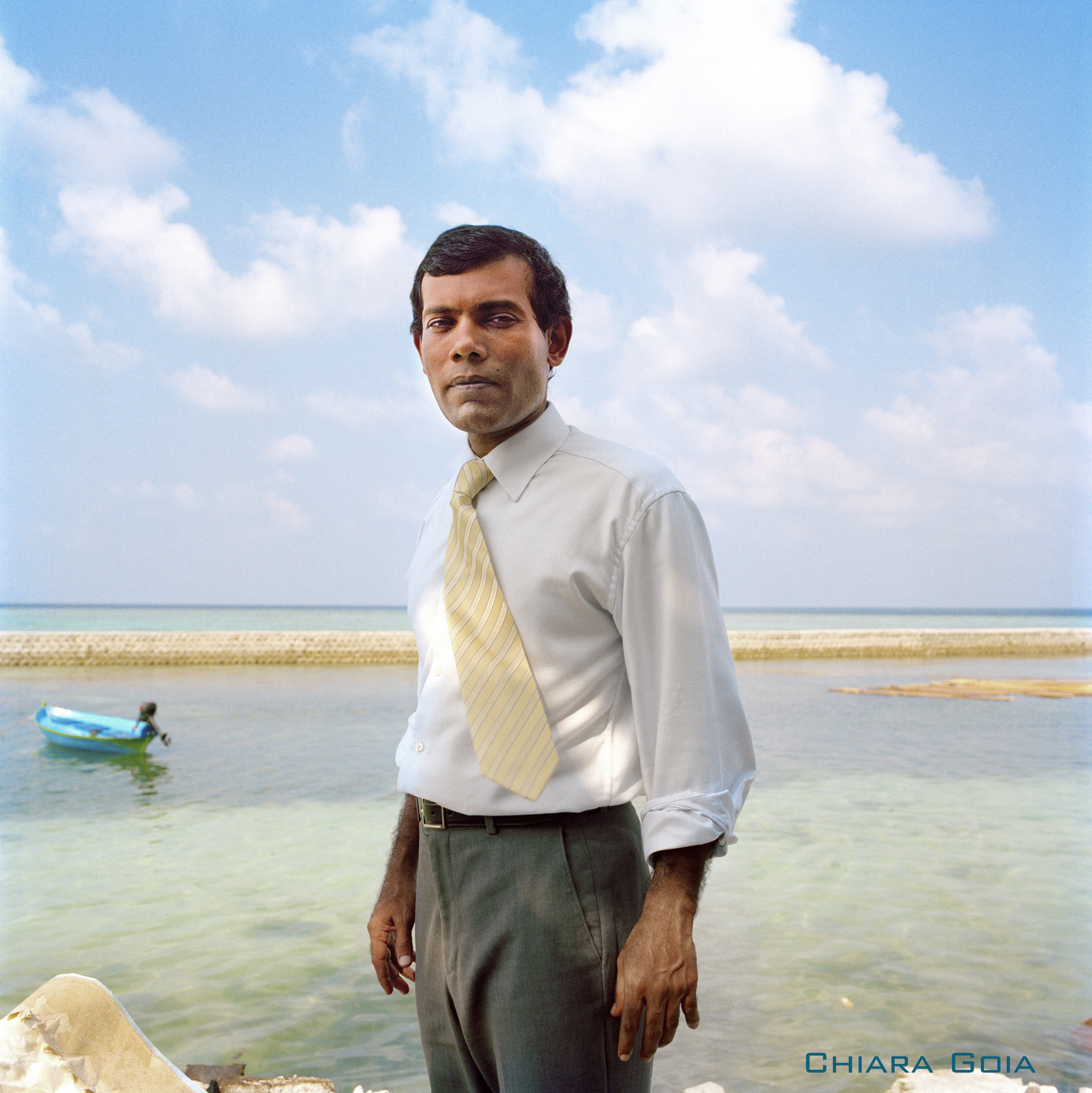

The Island President, a film by Jon Shenk about Mohammed Nasheed, the former President of the Maldives, and his fight for climate justice. Shenk followed Nasheed from his election in 2008, which overthrew 30 years of dictatorship under Maumoon Abdul Gayoon, through the COP 15 climate change talks in Copenhagen in 2009. There, he was an impassioned advocate for the future of his country, a low-lying archipelago, vulnerable sea level rise.“What is the point of having a democracy, if you don’t have a country,” Nasheed asked, launching his battle to instill the reality of climate change to his fellow heads of state. Nasheed reminds us that Male, the capital of the Maldives, is no higher Manhattan. “What happens to the Maldives today is going to happen to everyone else tomorrow.”

Nasheed is a compelling leader, knowing how to think like a scientist and like a minister. We witness the tension between him and the leaders of other developing countries like India and China, who are reluctant to curb their emissions feeling it would unfairly limit their growth. By contrast, Nasheed committs the Maldives to becoming carbon-neutral in 10 years. While this alone will not be enough to save them, he states “At least we will die knowing we have done the right thing.” With rising sea levels, the only high ground to stand on is a moral one.COP15 essentially preserved the negotiating process, but the agreement that came out of it wasn’t the fair, ambitious and legally binding treaty that was desired.

COP16 in Cancun and

COP17 in Durban did not pan out either. “By now you all must be pretty fed up with governments,” Nasheed said to the crowd in the theater in New York last week.“By now you all must be pretty fed up with governments,” Nasheed said to the crowd in the theater in New York last week.But Nasheed is an optimist. “We can lose many, many battles, but we cannot lose the war,” he said. In the film, we learn about Nasheed’s past as a former political prisoner, locked in a shack in solitary confinement for 18 months. There, he said, he took long walks in his mind, even though physical space was restricted. We learn he was first arrested in 1990 for establishing a political magazine called

Sangu, which scrutinized the ruling dictatorship.I was curious to learn more about this magazine Sangu, bearing my nickname.

The Sunday Leaderprovided some context:

“The ‘Sangu’ which meant Conchshell which in South Asia has been traditionally used as a trumpet to make announcements. The quality of Sangu was heart breaking. It was loose rough cyclostyled paper clipped together but conveying the voice of freedom from the archipelago.”

More on it was found here:

“Sangu (Conch shell) was the only independent fortnight magazine published in the Maldives in 1990. With death threats to the editors Sangu survived till 6th issue. While 7th issue was in print, at Cyprea Print, NSS (National Security Services) and Police forces surrounded and raided the building; confiscating all copies in print including layouts. The next day Sangu was formally shut-down by the authorities.”

In February 2012, Nasheed was ousted in a coup, backed by the former dictatorship. Democracy Now! has a great interview with Nasheed explaining what happened, and his future plans to return in free and fair elections.

In order for any adaptation measures to be properly implemented, Nasheed believes democracy must be restored to his country. He also spoke to Mashable last week, about the potential for social media in bringing democracy to the Maldives. I’m wondering if now is the time to revive Sangu as an online magazine—a trumpet call for freedom, democracy and climate justice.

Over at Brighter Green, I wrote this post on the film, The Island President, former President of the Maldives, Mohamed Nasheed, and his defunct political magazine Sangu:

Over at Brighter Green, I wrote this post on the film, The Island President, former President of the Maldives, Mohamed Nasheed, and his defunct political magazine Sangu: