The Next Big Thing Project is traveling post where writers answer questions about their works in progress and tag others to do the same. Thank you Sunil Yapa for inviting me to participate. I look forward to your book.

So here goes. This is my next big thing:

What is the working title of your book?

What is the working title of your book?

Divining Water.

What genre does your book fall under?

Literary nonfiction. I often describe the book as blending memoir, history and reportage. I’m interested in the nexus of the personal and the political, what the fabulous Minal Hajratwala calls “intimate history.”

The work aspires to employ the language of a poet, the skills of a journalist/scholar, and the insights of personal experience. Two other writers I recently discovered whose work falls in this realm are Susan Griffin and Rebecca Solnit.

In A Chorus of Stones, Griffin argues:

“We are not used to associating our private lives with public events. Yet the histories of families cannot be separated from the histories of nations. To divide them is part of our denial.”

And in the introduction of the essay collection: Storming at the Gates of Paradise, Solnit writes::

“I needed to describe, to analyze, to connect, to critique and to report on both international politics and personal experience. That is, I needed to write as a memoirist or diarist, and as a journalist , and a critic—and these three voices were one voice in everything except the conventions that sort our experience out and censor what doesn’t belong… Since then, I have been fascinated by trying to map the ways that we think and talk, the unsorted experience where in one can start by complaining about politics and end by confessing about passions, the ease with which we can get to any point from any other point. Such conversation is sometimes described as being “all over the place,” which is another way to say that it connects everything back up.”

My work in progress often seems “all over the place,” but the writing is rooted in these intersections of form and content.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

As a writer, this is the question I dread the most. This reluctance to answer has several components. Part of it is the fear that reducing the work into a single sentence reduces the work—that it cheapens and commodifies it. Another part is just the difficulty of the task- to summarize years of work that is seemingly “all over the place.” Rather than provide clarity and insight, the fear is that I’ll be misunderstood. And the last part of it has to do with the unknown. Many assume that in writing nonfiction, the story is already there, but I’m constantly discovering new things that complicate and drive the story into unchartered terrain. It is one of the joys of writing, but it can be difficult to summarize whenI’m still finding my way.

So with that I’m going to allow myself to ramble here for a bit. Divining Water is a story about three generations reconciling violence and disparity and their search for nonviolence in the modern world. I am researching the life of my paternal grandfather, who was stationed as a civil engineer in Burma from 1919 to 1934, when he had a radical shift, and decided to quit the British, give up all worldly possessions and join the Freedom Movement in India. He moved his family to the rural town of Kallakurichi, where my father, the youngest of thirteen children, was born. There, my grandfather became a water diviner and developed wells in the surrounding villages.I never met my grandfather, but like him, I studied civil engineering, worked on water supply projects and pursued social activism. I left my engineering job to work for a magazine called Satya, which was inspired by the Satyagraha movement that influenced my grandfather.

As an engineer, I studied hydrology and geology. I wanted to understand how the earth responds to human pressures. My stories here are set around rivers: Ganga, Gaumukhi, Yamuna and the Irrawaddy. Understanding the history and fate of these rivers also serves as a lens through which to examine larger social and environmental issues— both in my forbearers’ time and mine. The book is about losses (personal, political, environmental) and if/how we can recover from them. It is about the linkages between sanitation and social justice. It also examines the tension in the choices we make between family responsibilities and social activism.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The first fragments of this book were written long before I knew I would be writing a book. “Our journey began in North India, but this story really begins in South India, in a place called Kallakurichi, where my father was born…” began a letter I sent to friends after immersing my father’s ashes in the River Ganga.

Losing a parent leaves you with many questions. My father’s death in 2003 had set me on two parallel journeys, one that sought the unearth the past, and another that tried to understand the present. But it would be several years before I would revisit these pages. Nancy Rawlinson, a former writing instructor of mine, suggested I consider writing a book. I let that idea sink in and applied to the MFA program in nonfiction at Hunter College in 2008 with a proposal to work on this project. Prior to this, the various aspects of my life-—family, engineering, and activism were compartmentalized. It has been through writing that I’ve found ways to integrate them, and the idea for the book has since evolved.

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Still working on it. I had a good start with my MFA thesis, “Earth, Water Animal.” Since then, I’ve been slowly continuing on the journey of writing and research, while juggling a day job and other writing projects. Most of my writing these days occurs during my daily subway commute and vacation days. I recently received a Literature Travel Grant from the Jerome Foundation for this project to do so some research in London and Burma, where I’ll be traveling soon. (Thank you Jerome!)

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Hmm…Good question. I’m working on how to do justice to my characters on the page, and I’m not sure yet who would serve them well on the big screen. Suggestions welcome.

Who or what inspires you?

I’m inspired by people who pursue their passions and live their truths. I am inspired by acts of compassion. I’m inspired by the natural and the urban world, and the many creatures within them.

Who’s next?

I’m grateful and honored to have many wonderful writers in my life. Here’s a start. I can’t wait for your books and your interviews. Tell us about your next big thing Emily Bass, Laura May Hoopes, Amy Jo Kandathil, Parul Kapur Hinzen, Geeta Kothari, Anna Marrian, Cynthia Polutanovich and Krystal Sital.

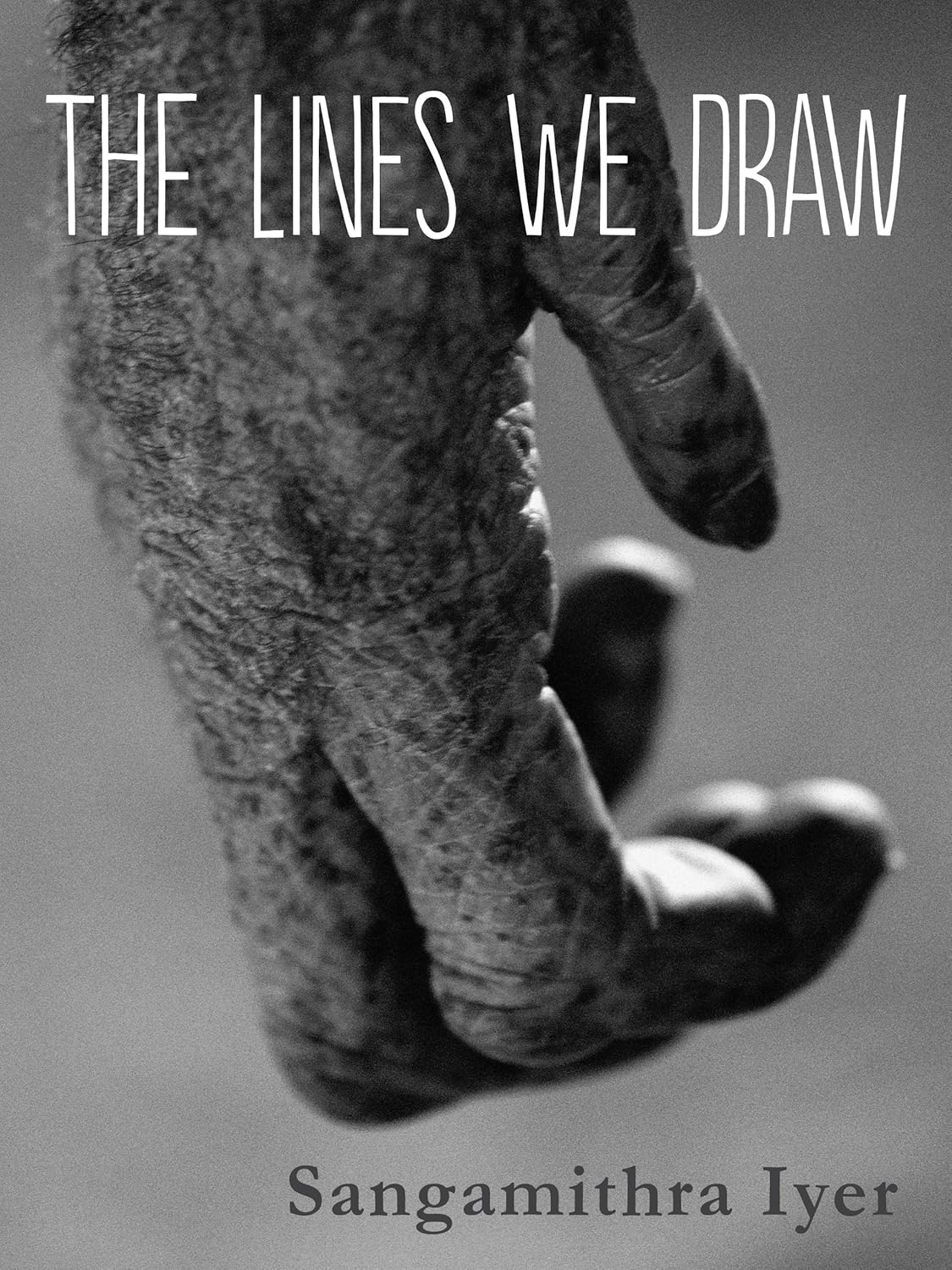

I am beyond excited to announce that my longform nonfiction narrative story “The Lines We Draw” has been published as a short ebook by Hen Press, the new digital publishing arm of Our Hen House. I can’t thank Our Hen House enough for their support, keen insights and feedback on this piece. About this story:

I am beyond excited to announce that my longform nonfiction narrative story “The Lines We Draw” has been published as a short ebook by Hen Press, the new digital publishing arm of Our Hen House. I can’t thank Our Hen House enough for their support, keen insights and feedback on this piece. About this story:

Gardiner Harris, the South Asia Correspondent for the New York Times, recently offended many Indian Animal activists with his story ”

Gardiner Harris, the South Asia Correspondent for the New York Times, recently offended many Indian Animal activists with his story ”  We started

We started  Sometimes the situation changed, the setting changed, the sky changed. We’d walk along the beach and discuss each other’s work. Ami shared with us a practice Ken Chen, head of

Sometimes the situation changed, the setting changed, the sky changed. We’d walk along the beach and discuss each other’s work. Ami shared with us a practice Ken Chen, head of