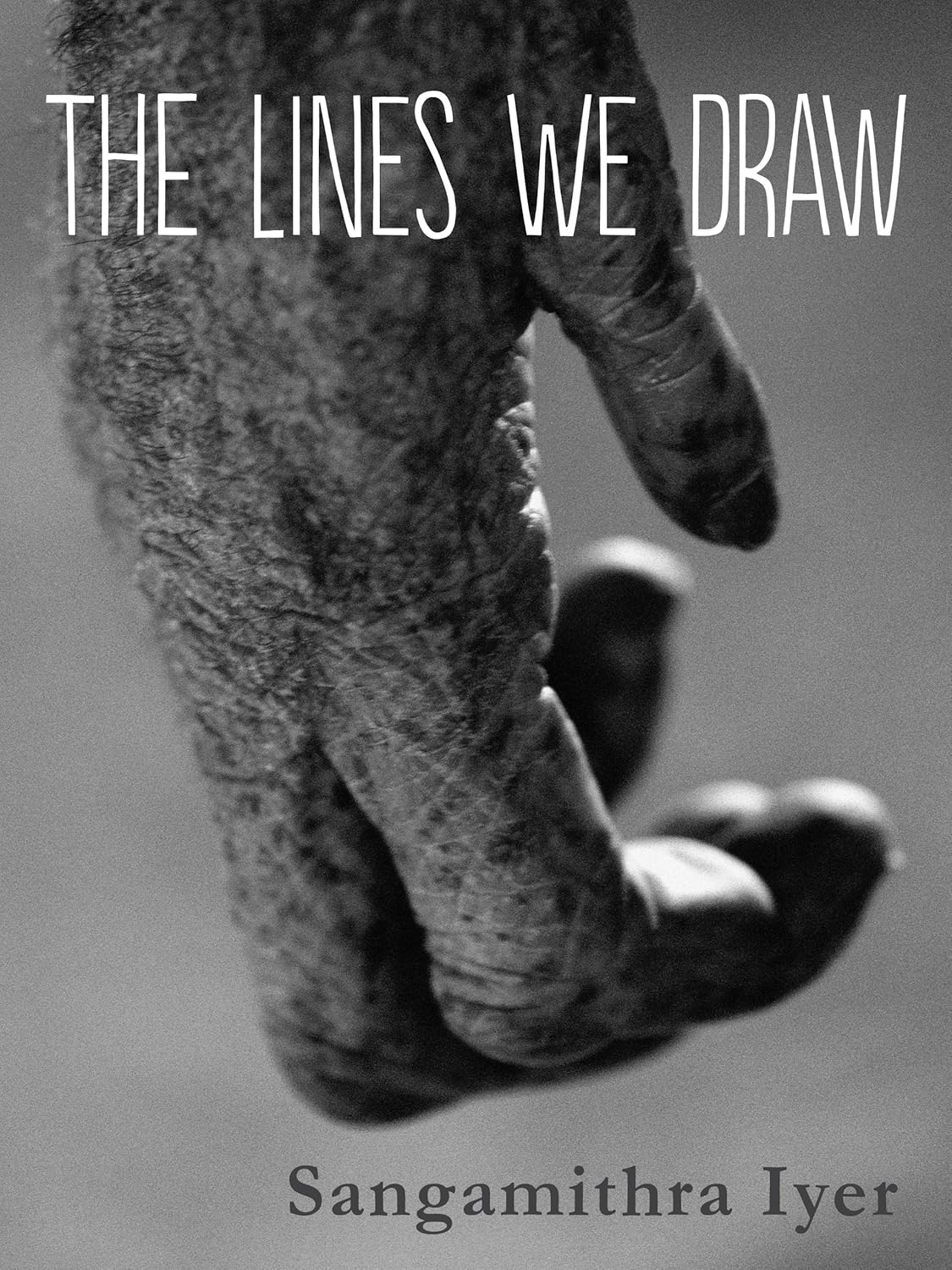

I am beyond excited to announce that my longform nonfiction narrative story “The Lines We Draw” has been published as a short ebook by Hen Press, the new digital publishing arm of Our Hen House. I can’t thank Our Hen House enough for their support, keen insights and feedback on this piece. About this story:

I am beyond excited to announce that my longform nonfiction narrative story “The Lines We Draw” has been published as a short ebook by Hen Press, the new digital publishing arm of Our Hen House. I can’t thank Our Hen House enough for their support, keen insights and feedback on this piece. About this story:

“This is story about boundaries — physical, biological, and ethical — it evolved out of a conversation with the late Dr. Alfred Prince, a hepatitis researcher, about the use of chimpanzees in medical research, and expanded into a larger discussion about ethics. Prince left New York University’s Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates (LEMSIP) in the 1970s to establish New York Blood Center’s chimpanzee research colony in Liberia. The story weaves various threads and makes connections among logging, the Liberian Civil War, and vivisection. Chimpanzees are slowly being phased out of research in the United States, and the New York Blood Center has ceased testing in Liberia, but questions remain about the fate of laboratory chimpanzees.”

You can purchase and download the eBook, The Lines We Draw, on Amazon, iBooks, and Barnes & Noble.

Would love to hear your thoughts.

MEDIA

- On February 22, 2014, on episode 215 of Our Hen House podcast, I spoke with Jasmin Singer and Mariann Sullivan about the piece and read a short excerpt.

- Pickles & Honey reviewed the story as part of their End of Week Reading.

- Viva La Vegan featured an short interview with me about the piece.

- One Green Planet features my story on the status of Chimpanzees in Laboratories.

- Mark Hawthorne, Author of Bleating Hearts: The Hidden World of Animal Suffering & Striking At the Roots discusses the ebook with me here. We had a lovely chat about writing about animals.

“Sangu’s resulting narrative offers a heady dialogue—the animal activist and the animal exploiter—but Sangu handles it with aplomb, and her writing is sometimes more poetry than prose.”

- I discuss the e-book with Jasmin and Mariann on the Our Hen House TV Show at Brooklyn Independent Media.

- The Aerogram features my Quick Picks.

For more of my primate memoir writing, check out Sister Species: Women, Animals and Social Justice (University of Illinois Press) and Primate People: Saving Nonhuman Primates through Education, Advocacy and Sanctuary (University of Utah Press).

See more of my work here: