“The impulse to write a book appears to run like a fever through those of us who’ve lived with apes,” declares Rosemary Cooke, the narrator of Karen Joy Fowler’s recent novel We are all Completely Besides Ourselves. Rosemary goes on to list those who came before her: “The Ape and the Child is about the Kellogs. Next of Kin is about Washoe. Viki is The Ape in Our House. The Chimp Who Would be Human is Nim.”

“The impulse to write a book appears to run like a fever through those of us who’ve lived with apes,” declares Rosemary Cooke, the narrator of Karen Joy Fowler’s recent novel We are all Completely Besides Ourselves. Rosemary goes on to list those who came before her: “The Ape and the Child is about the Kellogs. Next of Kin is about Washoe. Viki is The Ape in Our House. The Chimp Who Would be Human is Nim.”

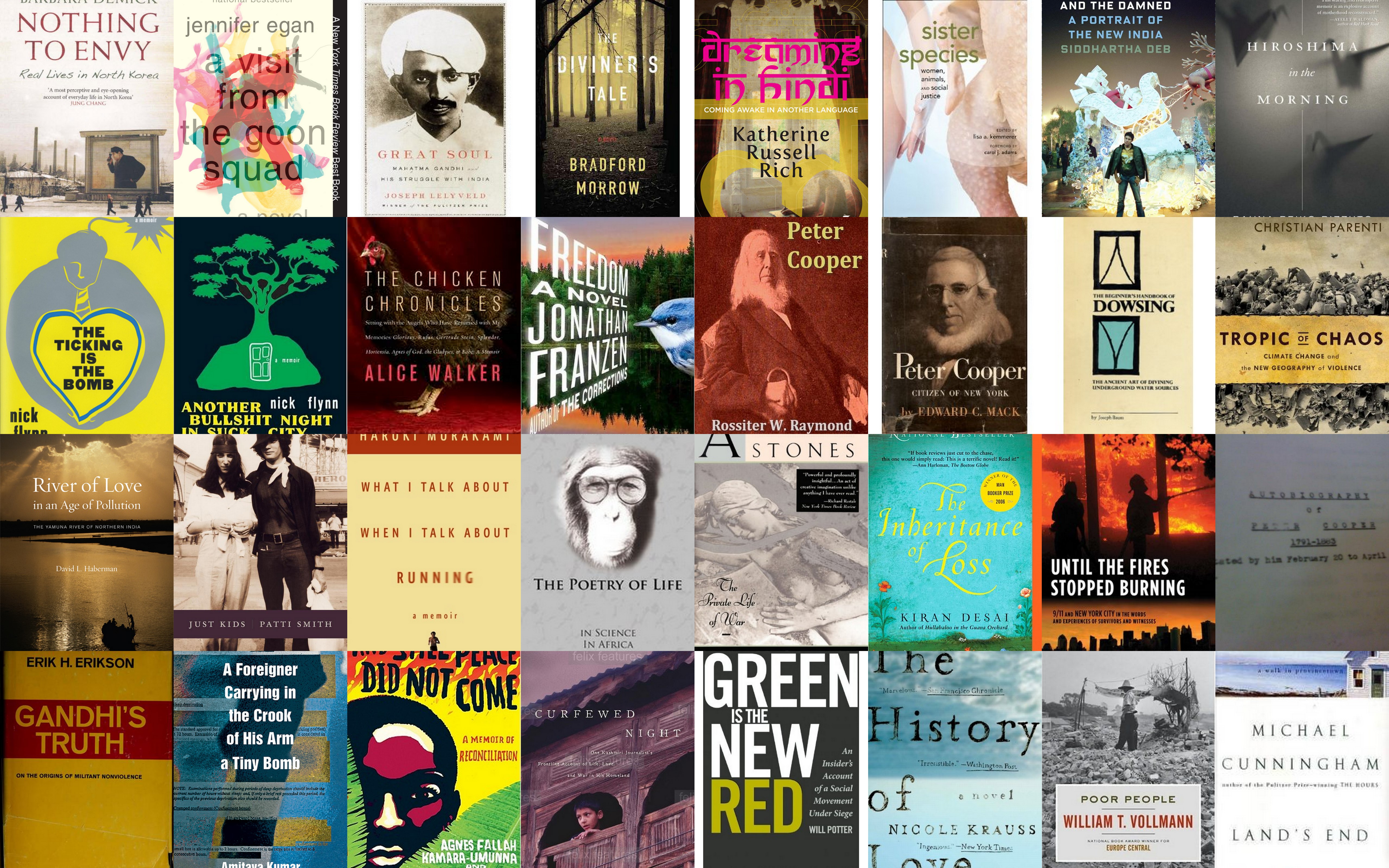

I’m no stranger to the genre of primate memoir, particular the stories of chimpanzees who were cross fostered and raised as human children to participate in language studies. I read Roger Fouts’ Next of Kin in college. It inspired me to learn American Sign Language and spend a summer with Washoe, Moja, Tatu, Dar and Loulis in Ellensburg Washington. It was at the Chimpanzee and Human Communication Institute that I was then introduced to others who had spent their lives among apes. Like Rosemary, I discovered Leakey’s women: “…I checked out every book, I could find on the monkey girls‑Jane Goodall (Chimps), Dian Fossey (gorillas), and Birute Galdikas (orangutans)”

Years later, I read In the Kingdom of Gorillas, before a trip to Rwanda. When discussing primate memoirs, I cannot forget to mention Robert Sapolsky’s A Primate’s Memoir, which opens with the line: “I had never planned to become a savanna baboon when I grew up; instead, I had always assumed I would become a mountain gorilla.”

Fowler’s novel is a fictional primate memoir, but hers is not the story of a researcher and his/her subject, but rather about the fate of the human children of researchers who were raised, briefly, with a chimpanzee. There’s not too much known about the human siblings of these cross-fostering experiments. Donald Kellogg was raised with the chimpanzee Gua for the first 19 months of his life. His parents terminated the experiment when Donald started picking up chimpanzee vocalizations rather than Gua picking up human ones. Later in life, Donald committed suicide in his early 40s.

Fowler’s story is loosely based on the Kellogg’s experiment, but also draws from other chimpanzees’ stories. The Cooke Family is based in Bloomington Indiana, where the Kelloggs did their research several decades earlier. At the time of writing the book, Fowler didn’t know the Kellogg’s had another child. Their daughter contacted Fowler after the reading the book. In an interview with BookSlut, Fowler notes “She was born about the time the experiment ended, so she has no memory of it herself, nor would her brother, who was only nineteen months old when the experiment ended. But she feels strongly that it completely deformed her family.”

In the beginning of Fowler’s novel, the reader learns only that our narrator, Rosemary Cooke, has a mysterious sister named Fern who disappeared when Rosemary was 5 years old and an older brother named Lowell who left home when she was 12. Rosemary only reveals the fact that Fern is a chimpanzee about a third of the way into the book. She has her reasons for withholding.

“I wanted you to see how it really was. I tell you Fern is a chimp and, already you aren’t thinking of her as my sister. You’re thinking instead that we loved her as if she were some kind of pet.”

Over at

Over at  Coinciding with the release of Brighter Green’s Case Study on India,

Coinciding with the release of Brighter Green’s Case Study on India,

“Call me Grandma,” Kazue Sueishi told the intimate classroom that had filled to hear her story. Born in America, Sueishi returned to Hiroshima as a child with her parents. She recalled her parents talking fondly of America. In her nursery school, she remembered being asked to draw something. She drew something beautiful with lots of crayon colors, and when asked what it was, she said, “America”

“Call me Grandma,” Kazue Sueishi told the intimate classroom that had filled to hear her story. Born in America, Sueishi returned to Hiroshima as a child with her parents. She recalled her parents talking fondly of America. In her nursery school, she remembered being asked to draw something. She drew something beautiful with lots of crayon colors, and when asked what it was, she said, “America”

Every now and then, I read something that I immediately want to share with everyone I know. I had such an experience recently while reading the current issue of

Every now and then, I read something that I immediately want to share with everyone I know. I had such an experience recently while reading the current issue of