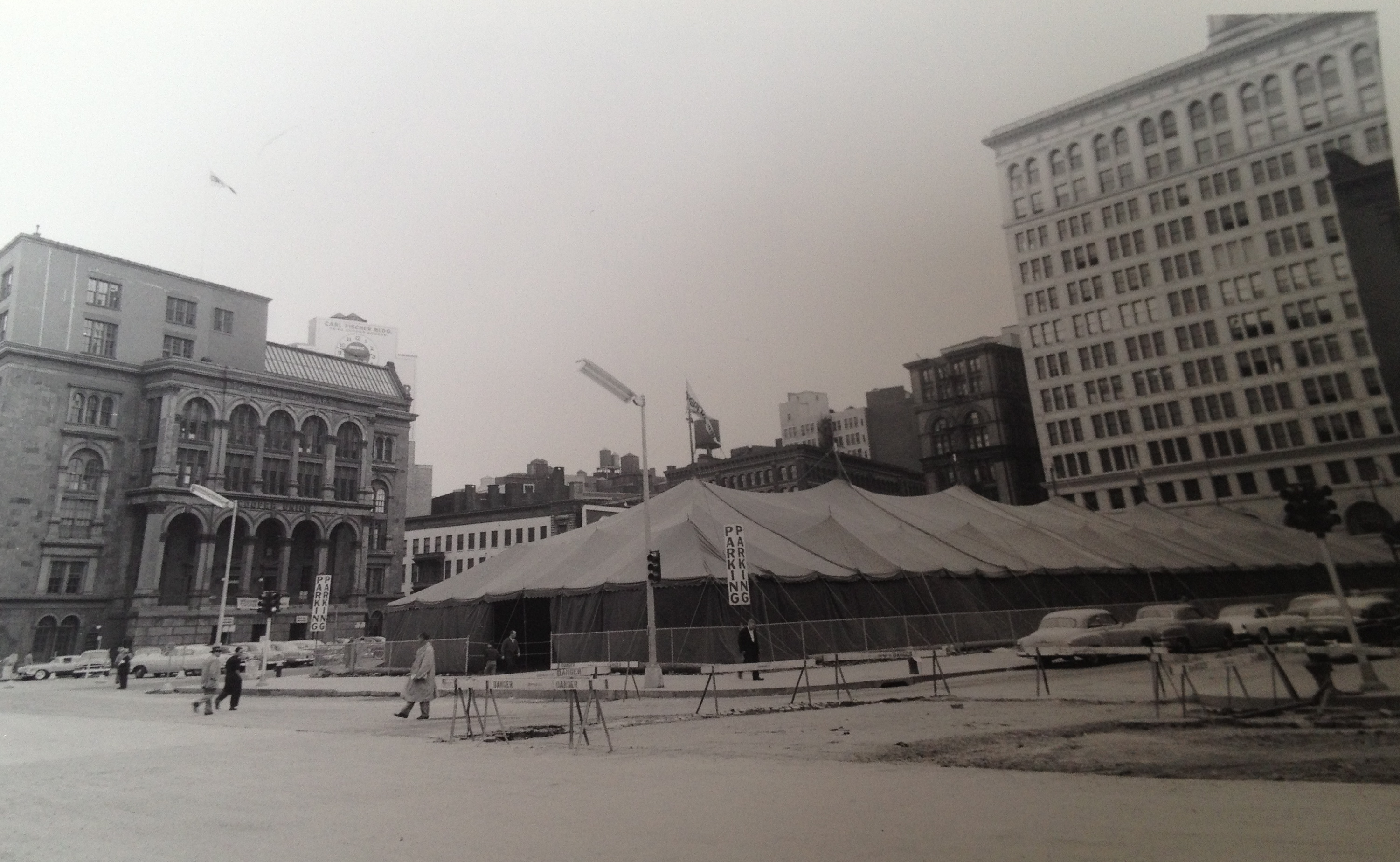

In speeches, radio interviews and meetings with alumni and stakeholders, Jamshed Bharucha, President of Cooper Union,has often brought up a lesser-known aspect of the school’s history: Cooper Union didn’t always provide a free tuition to all. In a speech last fall, he stated. “It is important to note that in the early years, approximately the first forty years, tuition was charged at Cooper Union. It wasn’t until 1902, when Andrew Carnegie made a large gift to the institution, that a tuition -free education was granted to students.”

In my meeting with the president and other alumni in December 2011, he reiterated this version of its history: “It was free for the working classes… It was never free for all until long after Peter Cooper was gone.” What Bharucha is referring to is a fraction of students in the female school of design, called “amateur” students who paid for their courses. He told us that “his [Cooper’s] actual policy when he was president was that those who could pay were charged.” But if you study the early documents, the extent, cost, context, and duration of the paying students in the early years are perhaps misrepresented in Bharucha’s narrative.

The first annual report discusses the amateurs in the School of Design for Women, the precursor to the school of art, (which later accepted male students in 1879):

“The instruction afforded in this school shall be given without charge, but the regulations may provide for the admission of amateur pupils for pay, so long as industrial pupils are not thereby excluded. All money received from such amateur pupils shall be applied to the support of the school…It will be perceived that in this school there is a departure from the invariable rule in the other department of the Union, that the instruction shall in all cases be entirely gratuitous. The Trustees were at first opposed to this deviation, but it was represented by the benevolent and enlightened ladies, who had established and maintained the school up to the time of its incorporation with the Union, that its character and usefulness would be impaired, if the wealthy and refined were entirely excluded from it; that the presence of ladies of leisure and refined tastes tended to raise the standard of art, and to give to the friendless associations of value in reference to their future careers. The Trustees, yielding to this argument, have limited the number of amateur pupils to one tenth of the total number instructed.”

Continue reading →

Primate People: Saving Nonhuman Primates through Education, Advocacy, and Sanctuary (University of Utah Press) comes out this month. I am very excited to read this anthology edited by Lisa Kemmerer with a forward by Marc Bekoff. My story “Soiled Hands” is the closing essay in the this collection.